By Valentina S . Grub

(Link)

Abstract

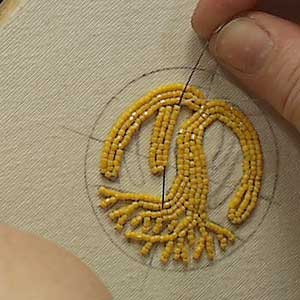

Medieval manuscript studies have been of increasing interest to the academe in recent years, and within the next year a book and an exhibition on opus anglicanum (English embroidery made between c. 1250-1350) are planned. Yet there has been little to no scholarship on how these two ‘minor arts’ intersect and interact. I am currently exploring records showing that there is evidence that some individuals were involved in both. In particular, mention of two nuns who were known as embroiderers and illuminators. I will look at both archival and artistic similarities, focusing on works between c. 1250-1350, when the English embroidery trade was at its height.